Women’s History Month Spotlight Amy Hallingstad

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Amy Hallingstad was a champion for civil rights causes in Alaska, desegregating schools and other public facilities, advocating for equal pay for women and quality health care for Alaska Natives, and tearing down signs that read “No Natives Allowed.”

She fought the most serious challenges faced by her people for most of her life, earning the unofficial title of “First Lady for the First People.”

And yet Hallingstad’s most powerful weapon in advancing these distinctly humorless issues was razor-sharp wit and unapologetic self-assurance.

“Now the men in Washington who are supposed to be our protectors say that big corporations can take our trees, our minerals and all our lands without asking our permission or paying us,” Hallingstad wrote in a letter to the newly formed National Congress of American Indians in 1947. She was seeking the support of the NCAI in addressing the violations of law and other agreements that allowed white men to take Native land and resources with impunity.

“… We are wondering if they expect us to live on snow and keep warm in the winter by burning ice.”

Hallingstad was born in Haines in 1901 and died in Petersburg in 1973. Her Tlingit name was Yax Yeidí, and she was Eagle of the Tsaagweidí (Split Killer Whale) clan and Aan Yakawlitseixi Hít (House That Anchored The Village). As a young woman she moved from Kake to Petersburg to join her parents, Sally (Jackson) Booth and Frank Booth, Sr. It was there that she later met and married her Norwegian husband, Casper Hallingstad, Sr.

The Hallingstads raised cattle and fished commercially while raising six children. In the early 1930s, their oldest child, Casper Hallingstad, Jr., started school and attended the segregated Native school in Petersburg.

Amy was incensed that Petersburg’s Natives were forced to pay taxes to support the whites-only public school but were not allowed to attend it. Her advocacy led to Casper Jr. being the first Alaska Native to attend public school in Petersburg.

“Amy was a woman remarkably ahead of her time in insisting on equality for Natives in civil rights, access to education and health care, pay for women, and labor reforms from the 1920s through the 1970s,” her granddaughter, Nicole Hallingstad, said. Nicole is the daughter of Casper Jr. and was raised in Petersburg, attending its public schools. Today she is a member of Sealaska’s board of directors.

“The depth and breadth of her advocacy legacy is not widely known,” Nicole said. “As Native people we are raised and taught not to speak of ourselves, so a lot of her information might be news to many people, especially younger people.”

Nicole said people tend not to know how many different issues her grandmother was active in. Amy advocated for equal pay on behalf of women working in the canneries in Southeast Alaska, helped establish the Mt. Edgecumbe School and Alaska Native Service Hospital, wrote the bylaws for Petersburg Indian Association, served as a delegate to the Democratic National Committee and as a representative for Alaska canneries with the AFL-CIO. Amy’s efforts expanded to Hood Bay, Excursion Bay, Pillar Bay and Chatham Straight to improve medical facilities and address needs of cannery workers. She joined the Alaska Native Sisterhood in 1919 at the age of 18 and later served seven terms as ANS grand camp president.

She was so politically influential that legendary Alaska politicians like Ernest Gruening, Bob Ziegler and Jay Hammond traveled to Petersburg to consult her about issues of importance to Alaska Natives.

“She was so intelligent, and she knew these communities and was able to be an important bridge and liaison between Natives and policymakers,” Nicole explained. So much so that Amy was propelled into a position on the Board of Fisheries, an extension of the US Fish and Wildlife Bureau, which was unheard of for a woman and especially for a Native woman.

Amy died when Nicole was 7 years old, but Nicole said Amy’s presence has been constant in her life. She still has distinct memories of her grandmother hosting visitors in her housecoat, cup of coffee in hand, as politicians and other political activists sought her input on the issues of the day.

“The thing that I remember most was that her house was always filled with laughter,” Nicole said. “She held so many organizing meetings in her home for the Alaska Native Sisterhood that my early years were spent listening to the stories and the strategies and just the roaring laughter of women working to make their lives better. I still have memories of her kitchen and that sense of knowing that people were doing important work – but also that they enjoyed each other and had such a passion for what they were doing.

“Amy fully embodied all her strengths and skills as exactly who she was in a time when women, and especially Native women, rarely had a voice. She used her voice unwaveringly for Native rights for decades and blazed a trail for so many others to walk, including me.”

Latest News

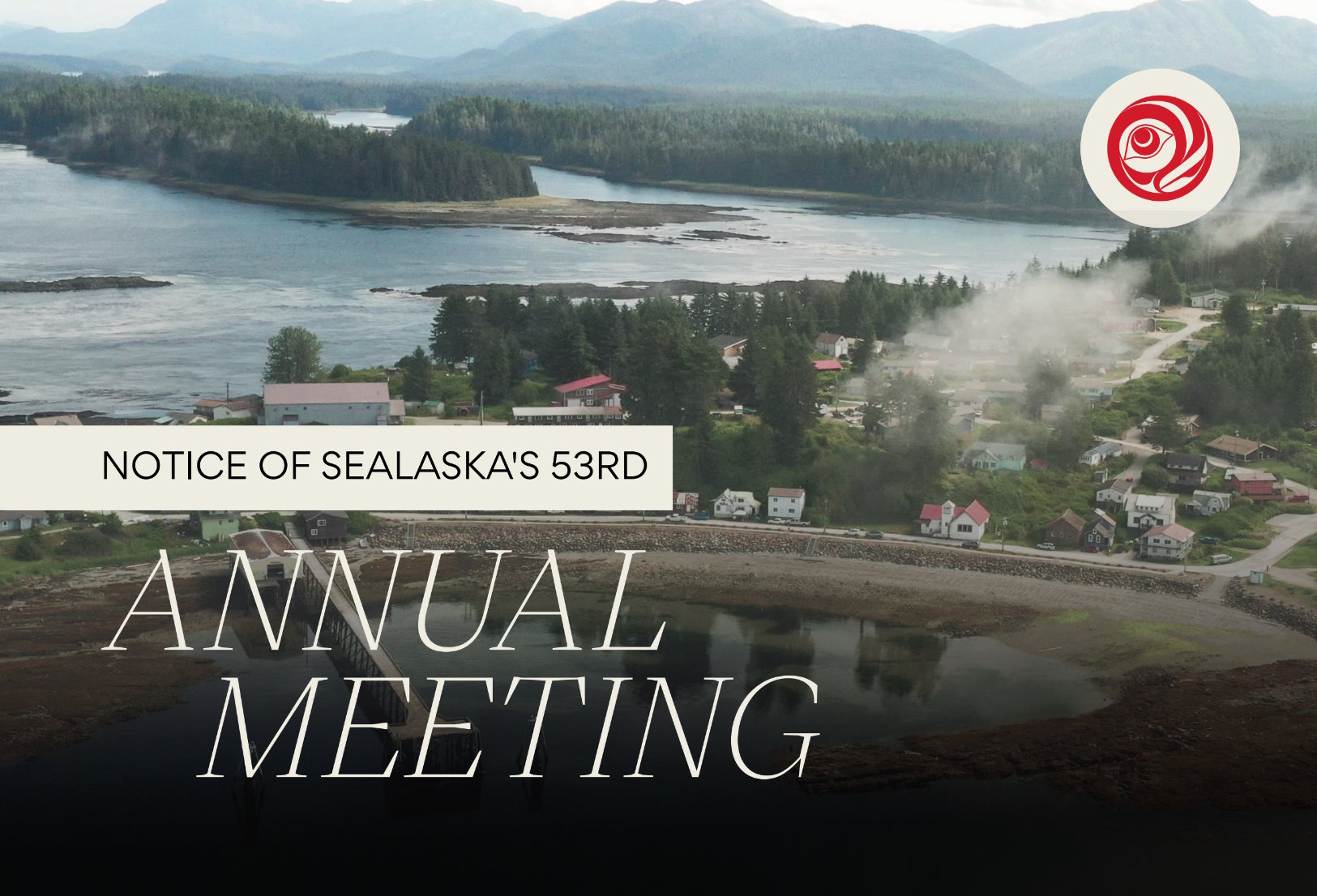

Notice of Sealaska's 53rd Annual Meeting of Shareholders

Pinned - Posted 2/12/2026The 2026 Sealaska Annual Meeting of Shareholders will be held on Saturday, June 27, in Angoon, Alaska. This year’s meeting will take place at the Angoon Elementary Gym, located at 500 Big Dog Salmon Road, Angoon, AK 99820.

Sealaska Welcomes Madeline Soboleff Levy

Posted 2/7/2026Sealaska welcomes Madeline Soboleff Levy as our new Vice President of Policy and Corporate Affairs.

Online Notary Service for Stock Wills

Posted 1/28/2026Sealaska is pleased to welcome Heather Shá xat k’ei Gurko

Posted 12/17/2025Sealaska is pleased to welcome Heather Shá xat k’ei Gurko as our new Director of Shareholder Communications.