Birth of Hawai'iloa

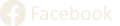

The Polynesian Voyage Society, recognizing the profound influence of voyaging on the revitalization of Hawaiian culture, embarked upon an ambitious quest to construct a traditional Hawaiian voyaging canoe. The vessel was named the Hawai’iloa in homage to the notable Polynesian voyager and original discoverer of Hawai’i. In their pursuit, PVS sought to build the canoe from Koa trees, the same material utilized by their ancestors, as a symbolic gesture of ancestral connection and cultural continuity.The Polynesian Voyaging Society dedicated nearly nine months to scouring the Kilauea Forest Reserve for Koa trees of an appropriate size and age. Their search was for more than just Koa trees of suitable size; however — it was a quest immersed in hope, hope that they would find an indication that the Kilauea Forest had not fallen into a state of irreversible decline. Unfortunately, the search exposed the stark reality that the once-thriving forests of Hawaii had been so depleted that no suitable trees could be found. Over the course of a century, these towering forests were reduced to a mere 10% of their former extent due to forestry practices and cattle grazing.

This realization imparted upon the Polynesian Voyage Society a profound lesson — one that underscores the interdependence of our cultural well-being and the health of our environment. It serves as a testament to the powerful bond that exists between the vitality of our cultural heritage and the preservation of our natural surroundings.

(Nainoa (center) with Shorty and Clay Bertelmann of Moku o Hawai’i searching for Koa trees, 1990)

A Gift from the Gods

During the 18th century, explorer George Vancouver arrived in Hawai'i. Upon seeing a majestic Hawaiian canoe, his curiosity led him back to the island where it landed, hoping to learn more about its origins and how it was built. Vancouver reported that it was the most remarkable canoe he had seen during his time in Hawai'i. He was astonished to learn that the logs used in the construction of the canoe were found drifting in the ocean, a divine gift in the eyes of the Indigenous Hawaiian people.From this story and others in Hawaiian oral tradition, we learn that the Hawaiians had another source of timber for their canoes: drift logs from the Pacific Northwest. These logs floated sometimes thousands of miles, carried by ocean currents, from the Pacific coast of the American continent – including Southeast Alaska to be embraced by the relatives across the sea who cherished them, utilizing these gifts to travel the Pacific in their remarkable canoes.

Armed with this understanding of the historical connection between Pacific peoples from Hawaii and logs from the Pacific Northwest, Herb Kawainui Kane and Nainoa Thompson connected with Tlingit Elder Judson Brown, who served as the chairman of the board of Sealaska. Kane and Thompson shared their project, its associated challenges and the depth of their mission with Brown, who demonstrated understanding and support. Brown, together with Sealaska President and CEO Byron Mallott, offered to provide trees from Sealaska lands to aid the Polynesian Voyaging Society in the construction of the Hawai'iloa.

(Construction drawings of the Hawai’iloa)

Tending to the Forests

Following an extensive search, Sealaska Forestry Manager Ernie Hillman succeeded in locating trees for the construction of the twin hulls of the Hawai’iloa. The Polynesian Voyage Society (PVS) made their way to Alaska, flying to Juneau, then by helicopter to Ketchikan and Prince of Wales Island, 80 miles into the heart of the forest, where the designated trees stood proudly. Despite the beauty of the trees and generosity of the gesture, Thompson could not shake a pervasive sense of unease that pervaded him. Unable to articulate the source of his discomfort, yet uncertain about moving forward without addressing the unshakable feeling. The others agreed. In solemn silence, they returned to Honolulu without the trees in tow to unravel the underlying cause of this hesitancy. Thompson sought counsel from the PVS board, his Elders and Hawaiian culture bearer John Dominis Holt. Their collective wisdom led him to a realization: as a people, they could not, at that moment, accept the gift of monument logs from Alaska, for doing so would feel like turning their backs from the pain and devastation inflicted upon their own forests. Before they could feel comfortable accepting this generosity from their relatives across the Pacific, they needed to confront the challenges facing the sacred forests of their homelands.The bond forged between Sealaska and the Polynesian Voyage Society captured widespread attention, shedding light on the decline of Hawai’i's Koa forests and sparking the growth of the Koa Reforestation Program. Through this formal initiative, spearheaded by the Kamehameha Schools, their students and the wider community, regular reforestation work began on the native forests of Keawewai. This focused emphasis on reforestation, as well as cultural and spiritual growth, was the start of a healing journey for both planet and people. Today, Hawaii’s forests now flourish with Koa trees on their way to reaching towering heights, ensuring that future generations may one day craft traditional canoes like the Hawai’iloa and Hōkūle’a from trees found on their homelands once again.

This progress toward reclaiming balance in Hawaii’s native forests, as well as an increased understanding of the interdependence between a healthy environment and thriving culture prompted Thompson to accept the gift of two colossal spruce trees for the construction of a new voyaging canoe after a few months of consideration.

Tlingit Elder and former Sealaska Board Chair Judson Brown, accompanied by Byron Mallott, the CEO of Sealaska, bestowed two magnificent Sitka spruce trees upon the Polynesian Voyage Society (PVS) after years of communication and partnership. Discovered within the U.S. Forestry land situated on Shelikof Island, in Soda Bay on Prince of Wales Island, both trees stood tall at a remarkable height of 218 feet, each with a diameter of 7 feet and were over 400 years old. To harvest the logs, Sealaska had to construct a special road to facilitate their transportation.

Tlingit leader Fran Houston delivered a solemn song entitled "Cha Dat Sa" before the trees were felled. The Hawaiians, in turn, raised their voices in a song known as "Ahu Nua", traditionally employed to seek permission. Finally, Tlingit Elders David Katzeek and Paul Marks performed the ancient tree-cutting ceremonies, calling upon the benevolence of forest relatives, seeking their approval to harvest the trees.

(Spruce logs delivered to Bishop Museum)

In 1993, the Hawai’iloa was completed, culminating in a momentous launch. As an expression of deep gratitude for the gracious gift from their relatives across the Pacific, the Hawai’iloa and its crew embarked on a voyage to Southeast Alaska during the summer of 1995. Reflecting upon this significant visit, Thompson recalled “In the construction and navigation of voyaging canoes by our ancestors, it was a collective endeavor that required the labor and artistic contributions of the entire community.” This is the legacy of the Hawai’iloa: it’s meaning transcends the boundaries of a single community, emerging as a testament to the strong relationships that have united our diverse Pacific peoples as "‘ōiwi," bound by common heritage and shared aspirations.

(Crowd welcoming Hawai’iloa at Sandy Beach, Juneau Alaska, 1995)

"When you sail, don't be afraid, because when you take your voyage, we will be with you. When the north wind blows, take a moment to recognize that the wind is our people sailing with you."

- Judson Brown to Nainoa Thompson, 1995

For additional information on Polynesian Voyage Society and the Moananuiākea Voyage, visit www.hokulea.com or follow @hokuleacrew on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube.

To learn more about Sealaska’s historical relationship with Polynesian Voyage Society, explore the links below:

A Voyage for Earth: This chapter follows the preparation and launch of the Moananuiākea Voyage, an ambitious journey of three canoes with a mission to unite Pacific communities and inspire a global education campaign centered on indigenous knowledge and ocean stewardship.

Regional Sailing Plan:Follow Hokulea as PVS voyages an estimated 43,000 nautical miles around the Pacific, visiting 36 countries and nearly 100 indigenous territories.

Uniting a Pacific Legacy: This chapter introduces the PVS and Sealaska’s historical relationship, highlighting the shared values and traditions that connect them across the vast Pacific Ocean.

Power of Cultural Exchange: This chapter highlights the enduring relationship between Hawai’i and Alaska Native communities, the ceremonies and traditions that connect them, and the lessons we continue to learn from one another.

Key Leaders Inspiring Generations: In the final chapter, the focus is on our ancestors that, to this day, continue to guide us with wisdom and deep belief in the traditional values of our people.

.jpg)