Inspiring Generations

United by our Indigenous identities, we reaffirm the deep-rooted connections and collective responsibility we bear in nurturing our shared waters, lands and planet as a whole. The dedicated efforts of Judson Brown, Byron Mallott, and Ernie Hillman reinforce the profound honor and pride we feel as we engage in collaborative efforts with the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS). These three leaders were crucial in welcoming PVS to Southeast Alaska. Hand in hand with our extended Pacific family, we have made remarkable strides in enhancing the well-being of both our peoples, strengthening our diverse cultures and languages and persistently breathing new life into our sacred lands and waters.Elder Judson Brown

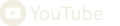

(Judson Brown (center) seated in Regalia, 1980)

(Judson Brown (center) seated in Regalia, 1980)

Judson Brown (1912-1998) was a Tlingit leader from Deishú (Haines), Alaska. He was Ch’áak (eagle), and from the Dakl’aweidi (killer whale) clan. His Tlingit names were Shaakakooni (Mountain Flicker) and Hinleiych (Yelling Sea Water), referring to the ‘woosh’ sound of the fast flip as the killer whale dives again after surfacing.

Brown’s father was James Wheeler Brown (K’ikaa, of the Kaagwaantaan). His mother was Mary Spurgeon Brown (Kaasanak, of the Dakl’aweidi). Notably, his heritage also included Native Hawaiian ancestry, forging a multifaceted identity.

Brown was a prominent leader during a critical moment in Alaska’s history, witnessing the transition from a time when Tlingit people lacked citizenship to the advent of ANCSA corporations and the emergence of globally recognized Indigenous cooperation and partnerships. In the face of prevailing prejudices held by white Alaskans, Brown’s innovative spirit helped him adeptly navigate the corporate world while maintaining his connection to culture and a profound reverence for Elders and ancestors. He stood as one of the first to recognize the importance of fostering connections between the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Pacific Coast and the Indigenous Hawaiians. With roots tracing back to both Aishihik and Hawaiian peoples, he was a warrior for the welfare of his people, while also championing the needs and aspirations of other communities. In 1990, during his tenure as the chair of the Sealaska Heritage Foundation, Brown forged a connection with Nainoa Thompson, who spearheaded the Polynesian Voyaging Society's transformative Hawai‘iloa project.

In his final years, Brown dedicated himself to honoring the legacy of his Elders and other culture bearers. As a self-taught ethnographer employed by Sealaska Heritage, he traveled Lingít Áani, tirelessly working to safeguard the stories and language of his people, consistently reflecting upon the profound contemplation of the strength and wisdom inherent in oral tradition. Through this journey of rediscovery, Brown and his peers recognized the profound importance of their own contemporary experiences, realizing the presence of spiritual giants who exemplified teachings throughout their lives. In a speech Brown reflected, "For some time, it was more popular to quote Aristotle and a few others from ancient times, but when we started going back into our own times and realized we had giants in spiritual strength, we realized we have always had this teaching by example amongst our people.”

(Red cedar house post in the Bishop Museum, carved by Nathan Jackson)

(Red cedar house post in the Bishop Museum, carved by Nathan Jackson)

In 1998, Sealaska gifted a remarkable 14-foot-tall Alaskan red cedar house post to the Polynesian Voyaging Society, serving as a tangible testament to the profound bond that has flourished between the Southeast Alaska and Hawai’i communities. The post currently rests in the Bishop Museum on O’ahu, serving as a timeless symbol of the enduring connection between the two cultures. Carved by master carver Nathan Jackson, this house post stands as a tribute to the memory of Brown, who passed in 1997. A closer examination of the Killer Whale carving reveals a remarkable detail —strands of human hair from an individual who shares both Hawaiian and Alaskan ancestry are delicately woven into its form, reinforcing the power of the relationship between our two Pacific peoples. The pole also features two male figures who symbolize the rich tapestry of Tlingit and Hawaiian cultures, standing as representatives of their respective communities.

Byron Mallot

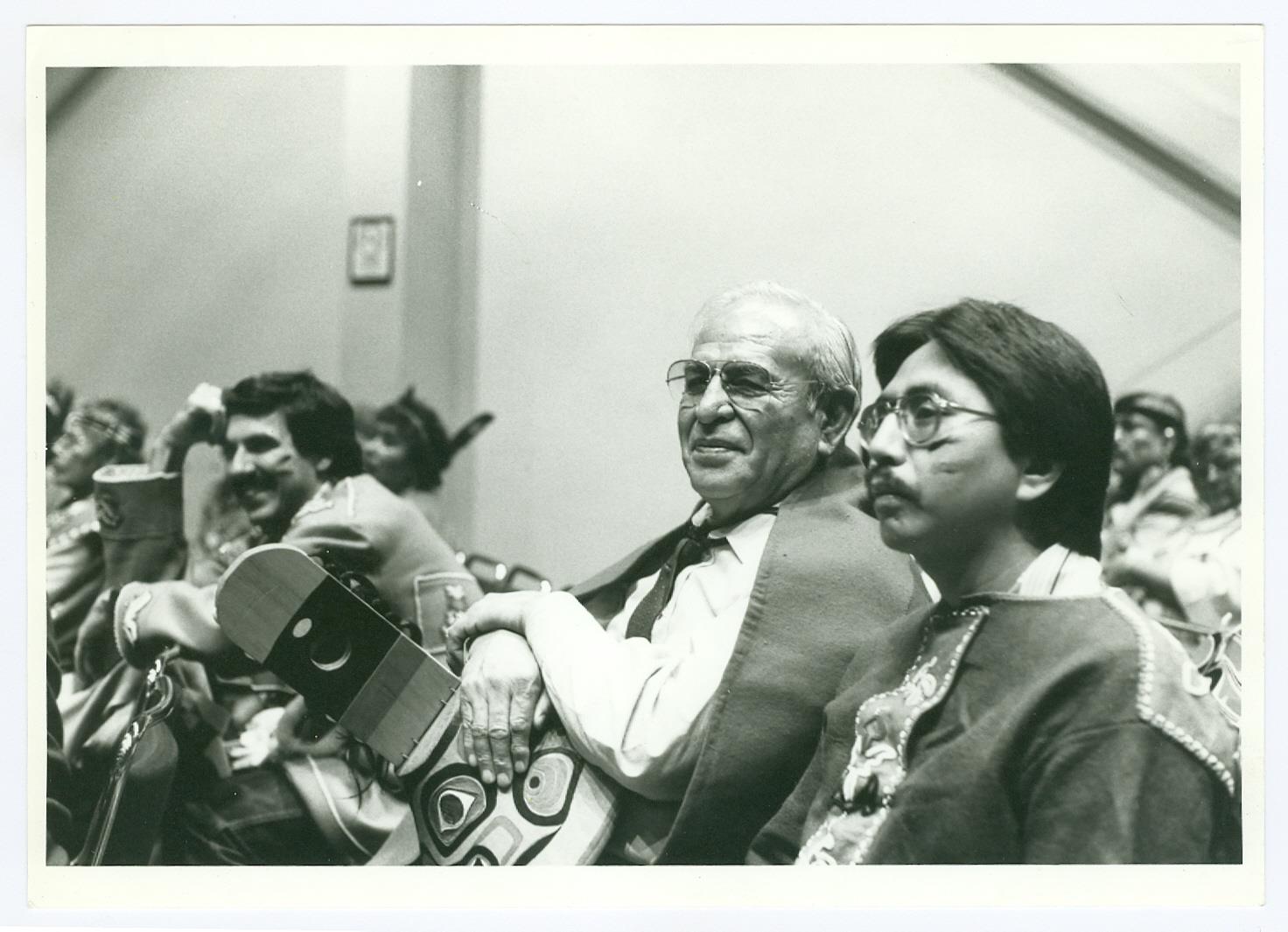

(Byron Mallott featured in January 1984 edition of National Geographic Magazine)

(Byron Mallott featured in January 1984 edition of National Geographic Magazine)

Byron Mallott (1943-2020), a visionary leader who served as one of Sealaska’s founding directors, and later, CEO, held an enduring friendship with the Polynesian Voyage Society. Mallott was Tlingit of the Raven moiety and a respected clan leader of the Kwaashk’i Ḵwáan of Yakutat. His Tlingit name was Dux̱ da neiḵ, K’oo del ta', which translates to “a person who would lead us into the future”. His profound care for and deep connection to the land were evident as he tirelessly advocated for Alaska Native land claims, working alongside other influential Native leaders to secure the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971. Mallott’s consistently prioritized the prosperity of Alaska Native people and the preservation of our vibrant culture.

Mallott's extensive involvement as a director, chairman, president and CEO of Sealaska played a pivotal role in fostering the enduring connection between Native Alaskans and Native Hawaiians. Mallott was deeply respected by the Hawaiian delegation and was asked to facilitate the acquisition of two trees from the Alaskan forest to help build the Hawai’iloa Mallott was the epitome of reciprocity, firmly declining all offers of payment and insisting that any logs used to build the canoe would be a heartfelt gift from Alaska to the Polynesian Voyage Society (PVS).

Ernie Hillman

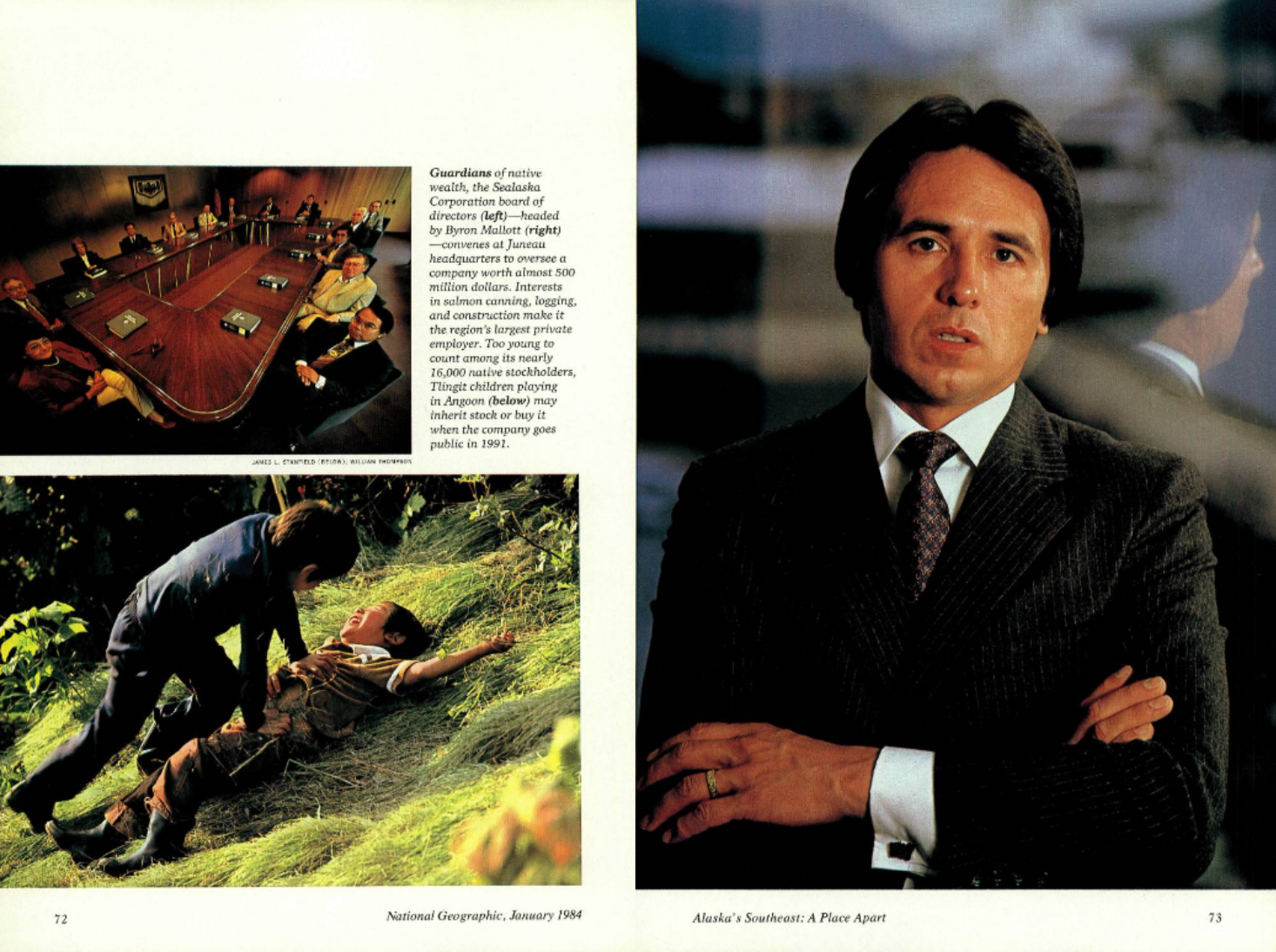

(Ernie Hillman (center) in Haines, 1995)

(Ernie Hillman (center) in Haines, 1995)

Ernie Hillman (1936-2018) was from Ḵuyeiḵ’ L’e.aan (Excursion Inlet) and served as Lands Manager at Sealaska. Ernie was Chookaneidi from the Glacier House, Child of the L'uknaxh.adi, and grandchild of the Deisheetaan. His Tlingit names were Khaalgheich, Chaas' Koogu Eesh, Chook'ank, and Khaaseiltseen. He was a pivotal figure in the relationship between Sealaska and our Hawaiian relatives. Through his role as Lands Manager, Hillman identified and assisted in the harvest of the two 400-year-old Sitka spruce trees that were instrumental in the construction of the Hawai’iloa in 1991. He had a long career in service to his people, which included working with the Tlingit & Haida Regional Housing Authority and helping to establish the Tlingit & Haida Regional Electrical Authority, serving as a magistrate judge in Sitka, and numerous other roles. Hillman’s life and legacy demonstrated a deep commitment to his community and the breadth of his contributions left an indelible mark.

For additional information on Polynesian Voyage Society and the Moananuiākea Voyage, visit www.hokulea.com or follow @hokuleacrew on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube.

To learn more about Sealaska’s historical relationship with Polynesian Voyage Society, explore the links below:

A Voyage for Earth: This chapter follows the preparation and launch of the Moananuiākea Voyage, an ambitious journey of three canoes with a mission to unite Pacific communities and inspire a global education campaign centered on indigenous knowledge and ocean stewardship.

Regional Sailing Plan:Follow Hokulea as PVS voyages an estimated 43,000 nautical miles around the Pacific, visiting 36 countries and nearly 100 indigenous territories.

Uniting a Pacific Legacy: This chapter introduces the PVS and Sealaska’s historical relationship, highlighting the shared values and traditions that connect them across the vast Pacific Ocean.

Birth of Hawai’iloa: This chapter follows the story of the creation of Hawai’iloa, the symbolic voyaging canoe that embodies the spirit of Polynesian exploration and the mission to care for the Earth.

Power of Cultural Exchange: This chapter highlights the enduring relationship between Hawai’i and Alaska Native communities, the ceremonies and traditions that connect them, and the lessons we continue to learn from one another.